Currency Hedging Can Boost Yields and Reduce Volatility

Key Insights

- Foreign currency bonds are often unattractive to U.S. investors because they offer very low yields or are perceived as carrying too much risk.

- By hedging the currencies of some foreign bonds, higher yields are obtainable—in many cases higher than the yields from U.S. Treasuries.

- Hedging the currency of emerging market bonds typically reduces the yield but can help to mitigate volatility.

With some foreign bonds offering very low/negative yields and others offering higher yields but also greater currency volatility risk, it is not surprising that many U.S. investors display “home bias” by allocating heavily to U.S. Treasuries. However, many of the perceived drawbacks of investing in foreign bonds can be overcome by currency hedging. In the current environment, hedging lower‑yielding global bonds back to the U.S. dollar can bring additional yield—meaning that U.S.‑based investors are effectively paid to hedge the currency risk of some global bonds. In other circumstances, currency hedging can be used to eliminate the volatility from foreign currency in higher‑yielding emerging market bonds.

With U.S. fiscal spending pushing deficits ever higher and the possibility of rate hikes further down the line, bond portfolios with heavy allocations to U.S. Treasuries carry considerable U.S. rate risk. Therefore, adding exposure to hedged foreign currency bonds offers significant diversification benefits as well as potentially boosting yields and mitigating currency volatility.

"...U.S.-based investors are effectively paid to hedge the currency risk of some global bonds."

How Currency Hedging Works

Currency hedging is a well‑established method of reducing the foreign exchange risk associated with investing in overseas assets. When investors hedge bonds, they typically enter a currency forward—a binding contract between two parties to exchange a certain amount of a currency for another currency at a fixed exchange rate on a specific future date. The use of the currency forward enables both parties to effectively “lock in” the exchange rate on a future transaction.

For example, a U.S. investor buying French bonds might enter a 12-month forward contract to sell euros and buy U.S. dollars equivalent to the amount of their exposure in order to hedge the French bond’s euro currency exposure back to the U.S. dollar. This is referred to as going “short” euros and “long” U.S. dollars. Often, these forward contracts are then “rolled” during the bond‑holding period—at or before expiration, the investor will compare the forward to the spot rate, settle up, and enter into another 12-month forward contract. The investor’s total return comprises the bond’s coupon (which is different from yield), any capital appreciation or depreciation on the price of the bond, and the net return from the currency forward position (often referred to as the “carry” from the hedge).

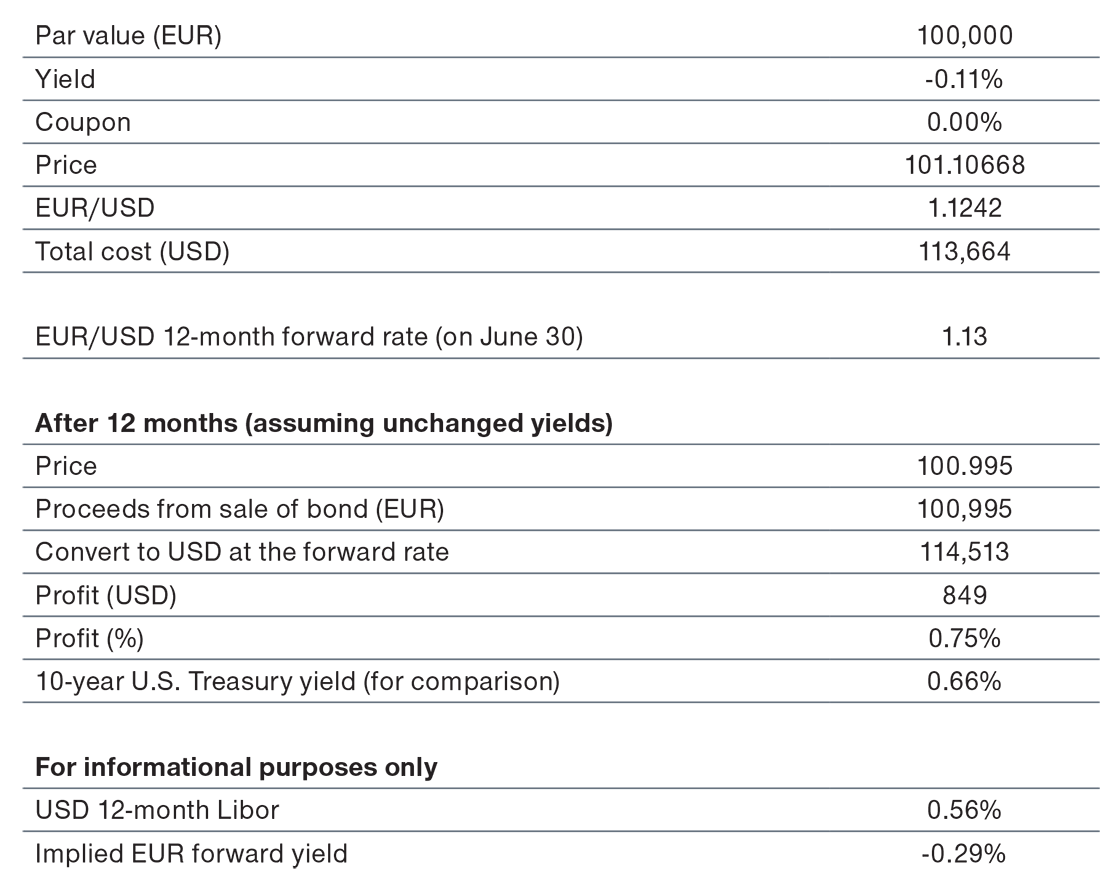

(Fig. 1) Hedging turns a negative yield into a positive one

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

The interest rate embedded in the forward foreign exchange rate is usually the difference between the short‑term wholesale interbank deposit rates of the two currencies being swapped. In the previous example, the euro deposit rate would be subtracted from the U.S. dollar deposit rate. As short‑term interest rates in the U.S. are currently higher than those of most other developed markets, there is a positive interest rate differential between the U.S. and most other developed countries.

Hedging to Boost Yield

To continue with our example, consider a U.S. investor buying and hedging French bonds. On June 30 this year, French 10‑year bonds yielded ‑0.11% at a “dirty” price (stated price plus accrued interest) of 101.10668. To purchase 100,000 French bonds, an investor would have required EUR 100,106.68 at the spot rate at the time of 1.1242, or USD 113,664. As the investor would have been selling a foreign currency at a negative rate and receiving positive yield on the local rate, they would receive “positive carry.” This would be equal to the implied euro forward yield of ‑0.29% (positive as the negative rate currency is being sold), plus the USD Libor of 0.56%—so 0.85% minus the negative yield of ‑0.11% from the French bond. Therefore, the net yield on the French bond would be 0.74% versus a 10‑year Treasury yield of 0.66%.1

"...the yields available to U.S. investors from hedged foreign bonds are substantially different from the unhedged yields..."

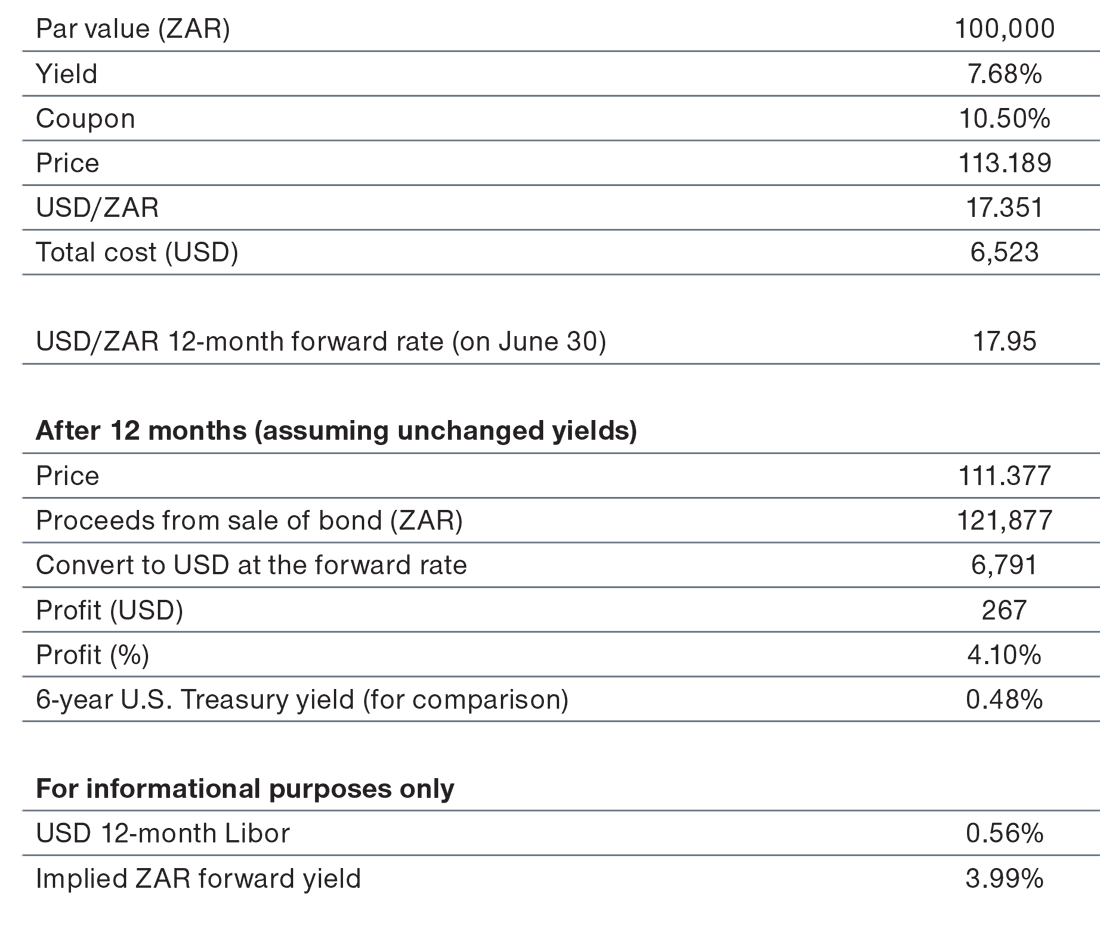

Hedging to Reduce Volatility

Now consider an investor looking at an emerging market local currency bond with a much higher yield—and greater volatility—than U.S. Treasuries. In this case, to hedge the volatility from currency risk would reduce the yield rather than boosting it as in the example of the French bond. Thus, an investor seeking to buy 100,000 South African bonds maturing on December 21, 2026, yielding 7.68% at a dirty price of 113.189, would need ZAR 113,189 or USD 6,523.

Assuming the investor wants to hedge all the bond exposure back to U.S. dollars, they will be able to sell the South African rand forward 12 months at a yield of 3.99%, effectively receiving U.S. Libor for 12 months at 0.56%. Therefore, the net cost of hedging would be 3.99% (the cost of hedging South African rand exposure) minus 0.56% benefit received from buying U.S. dollars 12 months forward, making a total net cost of 3.43%. Given the yield the investor receives from owning the bond is 7.68%, the effective yield (7.68% minus 3.43%) is 4.25%.2 Equivalent U.S. Treasury bonds maturing in December 2026 were yielding 0.56% on June 17. In this case, the hedged bond yields less than the unhedged bond but has much less volatility and is still greater than the U.S. Treasury bond.

(Fig. 2) The hedged yield is lower but provides stability

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

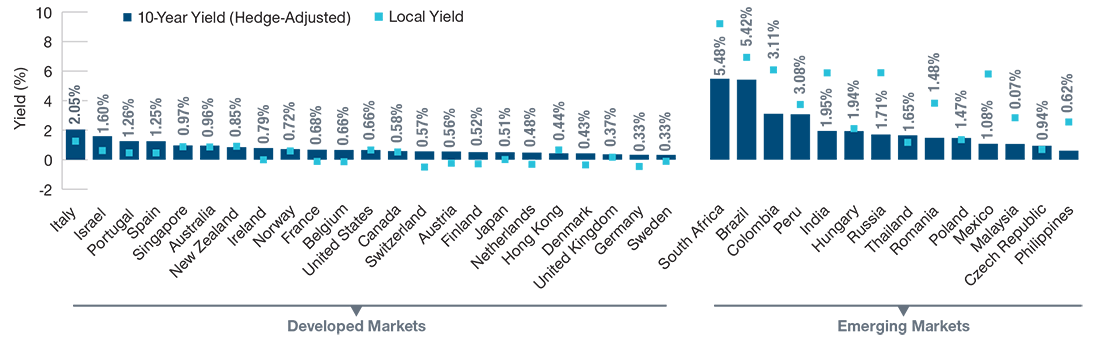

A Global Opportunity Set

To provide an indication of the global opportunity set, Figure 3 shows the yields of 10‑year bonds from various countries when hedged back into U.S. dollars on June 30. As the chart shows, the yields available to U.S. investors from hedged foreign bonds are substantially different from the unhedged yields (illustrated by the light blue squares) available from the same bonds. Typically, hedged yields are higher than unhedged yields for developed market bonds, while the reverse is the case for emerging market bonds. However, it should be emphasized that an attractive yield does not by itself provide a reason to purchase a bond—rather, it provides a signal that a bond is worth examining more closely. As yields move and prices fluctuate, fundamental research, combined with active portfolio and risk management, will be necessary to outperform market benchmarks.

HEDGED AND UNHEDGED FOREIGN BONDS OFFER VERY DIFFERENT YIELDS

(Fig. 3) Ten-Year USD‑hedged sovereign bond yields

The stated numbers are the 10-year yields (hedge-adjusted).

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Most U.S. investors have the majority, if not all, of their fixed income allocations in U.S. bonds, which means concentrated exposure to U.S. interest rate risk and the U.S. credit cycle. Many investors hear the words “global bonds,” and they think of negative yields or excessive currency volatility. But astute investors understand the benefits of using currency hedging to cast a wider net and invest in a larger opportunity set, finding higher yields, greater potential returns, and a reduction in portfolio risk.

WHAT WE’RE WATCHING NEXT

We will continue to monitor global bond yields, as well as currency movements, in order to determine where the best currency hedging opportunities lie. Concern over the coronavirus and its impact on the global economy may keep U.S. Treasury yields suppressed for some time to come. U.S.-based investors who are willing to broaden their fixed income portfolios to include foreign bonds with hedged currencies may be able to boost their returns and reduce portfolio risk.

1 Note the slight discrepancy here between the 0.74% hedged yield cited in the text (calculated by subtracting the net cost in percentage terms from the bond’s yield) and the 0.75% profit cited in the table (calculated by dividing the USD 849 profit by the USD 113,664 cost). The discrepancy here is due primarily to rounding.

2 In this example, the effective yield of 4.25% (calculated by subtracting the net cost from the bond’s yield) differs from the 4.10% profit cited in the table (calculated by dividing the USD 267 profit by the USD 6,523 cost). The discrepancy here is due to a number of issues, including the timing of the coupon, bid/ask spreads, and rounding.

Important Information

This material is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice or a recommendation to take any particular investment action.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of July 2020 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation, investment advice of any kind, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Investors will need to consider their own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., distributor, and T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., investment advisor.

© 2020 T. Rowe Price. All rights reserved. T. ROWE PRICE, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, and the bighorn sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks or registered trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.