5 Lessons From 5 Decades of Asset Allocation

Key takeaways

- Our asset allocation approach has drawn on our research over the past 44 years, research spanning five decades for which we’ve won 11 Graham and Dodd Awards.1

- In the early days, Ibbotson Associates pioneered strategic asset allocation based on rigorous research.

- Our asset allocation approach evolved when research pointed to the fact that expected returns vary over time in ways that are predictable, creating opportunities for investors to enhance returns. Today we call this valuation-driven asset allocation.

- Our history has taught us five lessons: 1) to be long-term minded, 2) to use a simple framework for assessing value, 3) to deeply assess fundamentals, 4) to think contrarian, and 5) to understand where you are in the capital cycle.

We are hosting a webinar on this topic on February 11th (at 1pm CT) and you can register directly here. Additionally, if you'd like to access the PDF of this insight paper, please click here to download.

The Asset Allocation Challenge in Brief

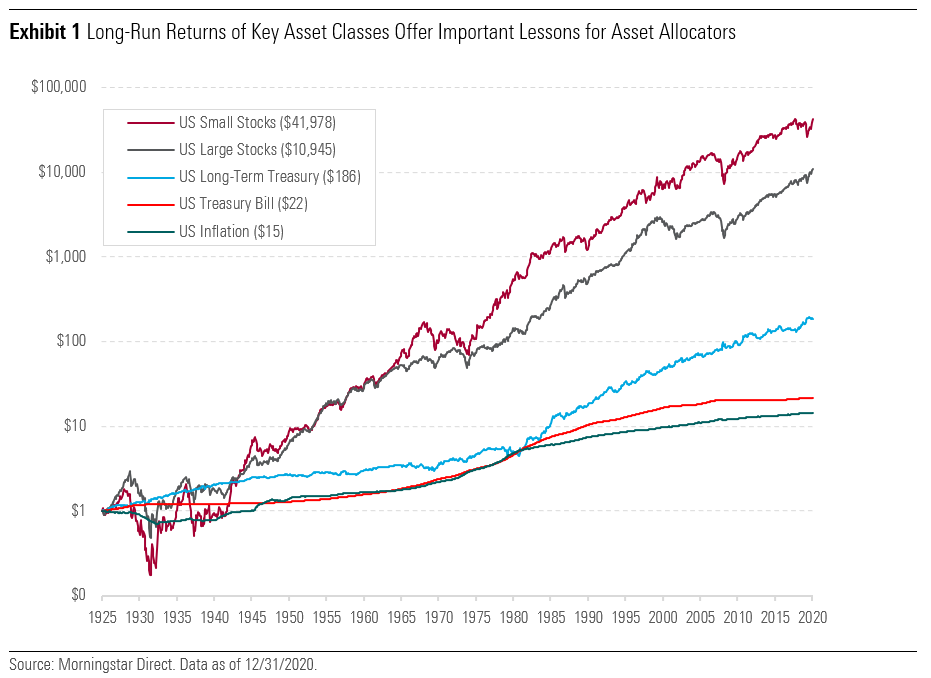

Our heritage traces back to the days of Ibbotson Associates,2 which was founded in 1977 by Roger Ibbotson, who also was the president of CRSP, the Center for Research in Security Prices at the University of Chicago. His early work documenting returns history grew into a cohesive approach to asset allocation, which Ibbotson Associates used to advise clients ranging from large pension funds to financial advisors. Along the way, Ibbotson Associates became synonymous with its yearbooks—the Cost of Capital Yearbook and its Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation (SBBI) yearbooks (the SBBI Valuation Yearbook, and the SBBI Classic Yearbook, which featured the growth of $1 chart that communicates at a glance the power of markets and compounding).

Together, Ibbotson’s yearbooks became the gold standard on how to value assets and combine them into portfolios. Meanwhile, his peer-review research pushed ever further into methods that sought to more accurately explain the corporate and economic fundamentals that drive long-term returns.

Of course, times change. Ibbotson Associates became part of Morningstar in 2006, before being integrated into Morningstar Investment Management in 2016. As a unified investment management team with personnel around the world, we had vastly larger resources to conduct in-depth investment research across a wide range of global assets. The research informing asset allocation best-practice also evolved, as work by Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller and others showed that when asset prices and fundamentals unlink, it can create risks and opportunities for investors. For us, that led us to develop methods for measuring how expected returns deviate from their long-run averages over time. Our current approach is geared toward opportunistically finding assets that are priced to deliver higher expected returns, while keeping a long-term perspective that traces back to our Ibbotson heritage. We call our approach valuation-driven asset allocation.

Through this evolution, some lessons have stood the test of time and continue to inform our best thinking today. We’ll unpack five key lessons that we believe are vital to be a great asset allocator today.

Lesson 1: It's Important to Keep a Long-Run Perspective

Long-term thinking dates back to Ibbotson Associates and even before. Benjamin Graham, the grandfather of value investing, said, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” Said another way, markets measure sentiment in the short term, but real value drives returns over time (see below for more on this).

In the SBBI Classic Yearbook, the “motivation” for creating the iconic Ibbotson long-run return chart was to “provide a period long enough … (to uncover) the basic relationships between risk and return among different asset classes … and between nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) returns.” Considering long-term data when estimating the fair return of an asset class allows one to separate signal from noise.

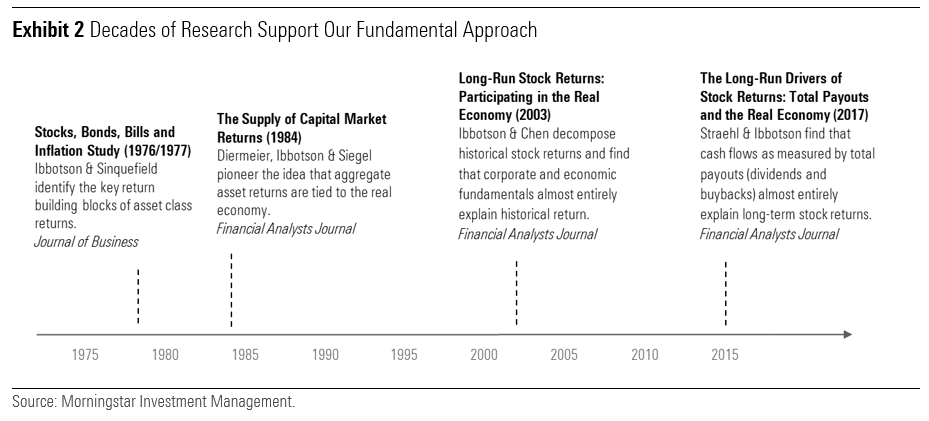

In the long-run, stocks outperform bonds and inflation. And for good reason: Roger Ibbotson illuminated this point in three follow-up studies that show that asset returns are intrinsically linked to the real economy (See Exhibit 2). Most recently, Roger Ibbotson and I (2017)3 demonstrated, using data from 1871 to 2014, that total payouts—which include both dividends and share buybacks—grew at a similar rate as the economy. In other words, equity investors participate in the growth that is supplied by the real economy, providing a fundamental explanation for why equity tends to outperform bonds in the long term.

Lesson 2: A Simple Framework Is Needed to Assess Value

The genesis of Ibbotson’s yearbooks were two papers he wrote with Rex Sinquefield in 1976. Using capital market data going back to 1926, the authors presented a framework for understanding asset class returns as the sum of two or more elemental parts—a building block approach. Jack Treynor called this approach “among the simplest that allow for the principal capital market phenomena.” Ibbotson later applied it to asset allocation.

In our asset class research today, we continue to use building blocks, which provides a framework for us to simplify the valuation of assets. For example, to value an equity market, our global investment team separately considers its 1) expected total payout yield, 2) expected cash flow growth, 3) change in valuation, and 4) inflation. These building blocks come together to create a single valuation-implied return estimate, which, when compared to its long-term or fair return, helps us decide whether the asset class is attractively priced.

Warren Buffett has a famous quote in this context: “To invest successfully over a lifetime does not require a stratospheric IQ, unusual business insights, or inside information. What’s needed is a sound intellectual framework for making decisions, and the ability to keep emotions from corroding that framework.” In this way, our valuation models provide our investment team with a simple and intuitive yardstick to assessing the attractiveness of an investment opportunity across global capital markets and help us stay rational during periods of extreme optimism and pessimism.

Lesson 3: Fundamentals Drive Asset Prices in the Long Run

Understanding the difference between price and value is an important point for asset allocators, albeit a contentious one. We take a pragmatic approach to this, informed by academic learnings and the gravitational reality that long-term prices are linked to long-term fundamentals.

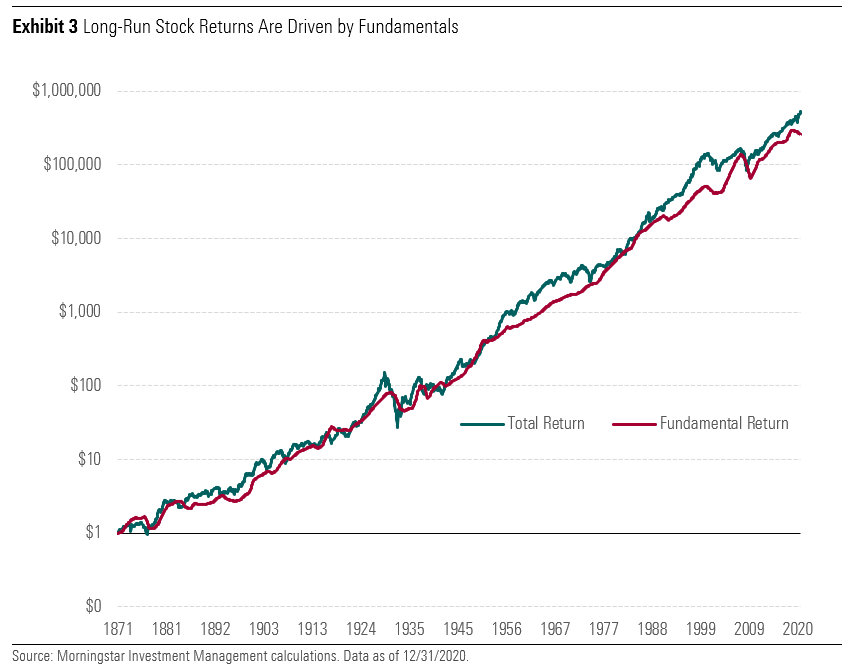

Looking somewhat differently at the long-run SBBI chart (see Exhibit 3), we see that in the very long-run equity returns are almost entirely driven by fundamentals as measures by the total payout yield and growth of total payouts.4 This insight puts the onus of long-term investing on a deep understanding of fundamentals. Thus, the focus of the valuation-driven asset allocation today is to gain an in-depth understanding of the assets that we invest in. Our asset class team5 of dozens of investment professionals help us uncover these opportunities around the world, as do the data and analysis from hundreds of analysts from Morningstar, Inc. and its subsidiaries.

The chart also highlights that there are times when total return has departed from the fundamental return. The gap between the two represents returns driven by sentiment, or changing risk-aversion, and they can either run ahead of or lag behind fundamentals. These are the periods that create opportunities for valuation-driven investors. Our approach is designed to buy assets when they are trading at a discount to their fair value, and underweight assets that trade at premium. Buying assets that offer high expected returns given our forward-looking estimate of fundamentals is the hallmark of our valuation-driven process.

Lesson 4: Fish Where the Fishermen Aren’t

Contrarian thinking is the third leg to the stool in our valuation driven asset allocation process. Given that investor sentiment can cause valuations to stray from fundamentals in the short to medium term, an investor needs to understand all three—valuations, fundamentals, and investor sentiment—to find opportunities.

In their research on the notion of popularity,6 Roger Ibbotson and Morningstar's Thomas Idzorek demonstrated that assets that have characteristics that are popular with investors, tend to offer lower expected returns compared to assets that are relatively overlooked. Supported by this research, we believe combining valuation with an understanding of investor behavior can increase success.

Famed value investor and Warren Buffett’s longtime business partner Charlie Munger famously said that the first rule of fishing is to go where the fish are. To the investor, that means you must understand an asset’s fundamentals. Carrying the analogy further, a large fishing hole covered by many fishermen doesn’t seem as ripe for success a small fishing spot with one fisherman. Saying there’s an optimal ratio of fish to fishermen is taking it too far, but that’s the general idea. And that’s what being contrarian is all about—finding the fish, yes, but also making sure you’ll be able to catch them before others do.

For us, we seek to stay disciplined not only in our fundamental and valuation work, but also in how we assess opportunities—every time we buy, another investor is selling, and we want to have as much confidence as we can that we’re getting the better deal. So, we study diversity in the market, investor sentiment as gauged by surveys and analyst consensus, and trading volume and liquidity. In other words, how many fishermen have already found the spot we believe to be promising?

Let’s face it, fishing—and investing—can be hard. The comic Steven Wright once said, “There’s a thin line between fishing and standing on the shore like an idiot.” We study the fish and the fishermen—fundamentals, valuations, and investor behavior—as a way to improve our chances of success.

Lesson 5: Understand Where You Are in the Capital Cycle

Disruption has become a hot topic in the last decade, but change is part of a longer evolutionary chain. Disruption has come in many forms throughout history, and it will likely evolve again. What the next disruptive force will be is unknowable today—but we believe that fundamental research aimed at understanding these disruptive forces is integral to a robust investment process.

While history is a useful guide for long-term investors, it’s important to remember Mark Twain’s insight that history doesn’t repeat itself, but often rhymes.

In our investment process, we examine change through the lens of capital cycle analysis. The capital cycle is based on the notion that industries with high profits tend to attract high capital investment, which drives down future profits. Said differently, high capital flows increase the supply of products and services in an industry, driving down prices. Lower prices, in turn, diminish profits, reduce the industry’s incentive to invest, setting in motion a start of a new capital cycle where new companies find ways to boost profits, thereby attracting more capital. We believe that understanding the flow of capital is important because it changes the risk and reward of an asset.

It was the application of this process to the Australian equity market that convinced us to steer clear of the mining boom in Australia that ended in the early 2010s, where strong Chinese growth led to a decade-long boom in commodity prices. This sent mining stocks to lofty heights, with enormous capital investment by mining companies who sought quick fortunes amid the commodity boom.7 For this reason, capital cycle analysis plays a big role in our process, which allowed us to detect the Australian mining boom.

Ready for the Next 44 Years

Clearly, much has changed in the past 44 years, but we believe these lessons have endured throughout. Some things never change or change very slowly, and investing is one such example.

We view successful investing as finding assets that trade at a discount to their instinct value. It sounds simple, but it’s not easy. The past five decades taught us that it requires a long-term mindset, a deep understanding of fundamentals, a repeatable framework for decision-making, a willingness to go against the crowd, as well as an awareness of the capital cycle.

We believe these lessons will serve investors well for the next 44 years and beyond, come what may, because they are time-tested and deal with the unchanging elements that drive returns.